Every second of every day, a battle of good and evil rages inside your body. The good is the immune system, armies of cells that defend the body from illness and infection. The evil comes in the form of the pathogens, viruses, bacteria and mutated cells that are programmed to do harm.

When the body fights cancer, the good guys don’t always win. Healthy cells require a complex combination of internal and external signals between enzymes and proteins to work properly and regulate their growth and division. When those signals go awry, the cells may run amok and grow out of control, forming a tumor.

But new immunotherapy treatments, emerging technologies and ongoing research are giving doctors more tools to help the immune system do the job it was meant to: fight back against threats like cancer. And researchers are learning more about how the immune system works, how cancer hides from immune cells and how some immune cells may actually be coopted to help cancer grow.

"Our immune system is designed to recognize native and non-native cells that can harm us,” says Stephen Lynch, MD, Intake Physician and Vice Chief of Staff at City of Hope Phoenix. “The problem is it doesn't always work. Other times, it works against us."

In this article, we’ll answer these questions:

- How does the immune system protect the body from disease?

- Does the immune system fight cancer?

- How may cancer immunotherapy help?

If you’ve been diagnosed cancer and are interested in a second opinion about your diagnosis and treatment plan, call us or chat online with a member of our team.

How does the immune system protect the body from disease?

The immune system is an efficient and powerful biological machine. Think of it as an invisible bio army that protects you from millions of germs and fights off viruses and infections. So powerful are its responses that they may cause fevers, aches and pains, inflammation and swelling.

“It’s because your immune system is ramping up—it’s doing what it’s supposed to do,” Dr. Lynch says. And it does more than fight off disease.”

In military terms, the immune system has two divisions: adaptive and innate.

Adaptive immune cells

These cells target viruses or bacteria, using information delivered from dendritic cells and other innate immune cells, and they store information about these pathogens so they can recognize and target them again should they launch another attack. The adaptive immune system—also called acquired immunity—is more sophisticated and may take days to develop a plan of attack.

There are two main types of adaptive immune cells, listed below.

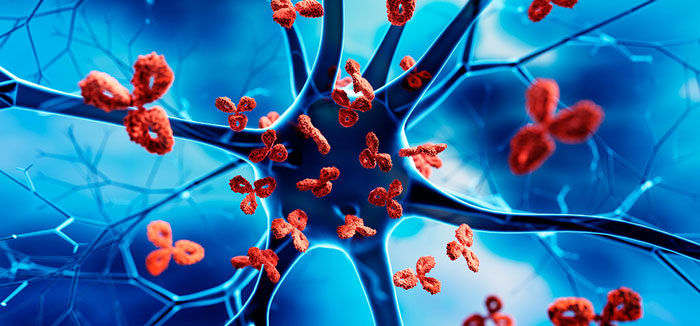

B-cells, which produce antibodies—Y-shaped proteins that fight bacteria. The antibodies latch onto the surface of an invading cell and mark it for destruction by other immune cells.

T-cells, which come in various forms, including:

- Helper T-cells, which stimulate an immune attack

- Killer T-cells which attack bad cells directly

- Regulatory T-cells, which help shut down an immune response when the job is done

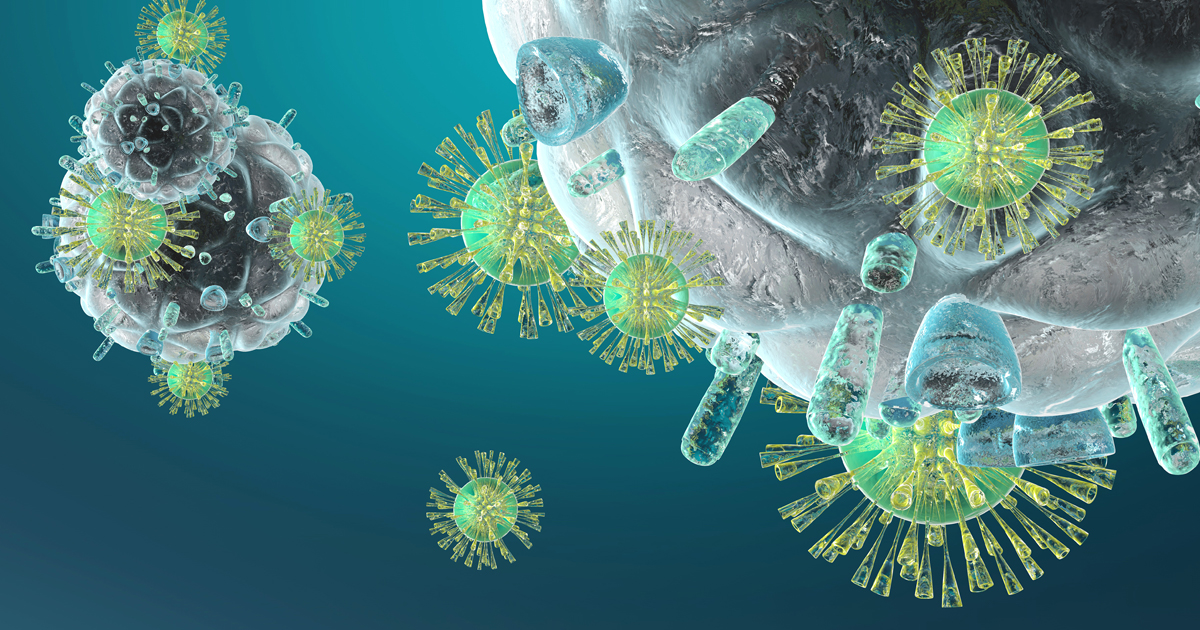

Innate immune cells

These immune cells are the body’s first line of defense, programmed to attack cells they sense as a threat to the host. Innate immune cells are designed to kill first and ask questions later, Dr. Jeffrey Weber, deputy director of the Perlmutter Cancer Center in New York City, quipped in a video lecture about the immune system

Among the cells in the innate immune system are those listed below.

Macrophages: Named for the Greek words that mean “big eaters,” these long-limbed cells are true to their moniker. They’re voracious, using flexible tendrils to snag and attack their targets.

Neutrophils: These short-lived cells are the first line of defense against infection. They kill bacteria, then die, forming pus.

Dendritic cells: These are the innate immune system's traffic cops, directing T-cells and B-cells to their targets.

Mast cells and basophils: They produce histamines that help the immune system attack allergens.

Researchers believe that immune cells do more than attack intruders and fight disease.

For example:

Researchers at Northwestern University have concluded that macrophages stimulate cells in the heart muscle, helping to keep the heart pumping and maintain a steady beat.

Swedish researchers have found evidence that immune cells clear out dead brain cells after a stroke and secrete substances that may allow the brain to repair damage.

Does the immune system fight cancer?

If the human immune system is so strong and sophisticated, why do nearly two million Americans develop cancer every year?

It may not be because of immune system failures. In fact, it’s likely that your immune system may regularly fight off cancer or pre-cancer on a regular basis without you even knowing it.

"The immune system is absolutely critical in fighting cancer," Dr. Lynch says.

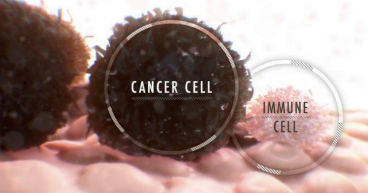

Also, the immune system is better designed to fight foreign cells that invade the body from the outside, such as bacterial and viral pathogens. Cancer cells are the body’s own cells that have gone rogue, and the immune system may not always see them as a threat.

When cancer cells thrive, it’s often because they:

- Evade or hide from immune cells using signals that healthy cells may use

- Shut down immune cells and sometime use them to proliferate

- Overwhelm or exhaust the immune system with sheer numbers and rapid growth

A fine balance exists between the burden of cell mutation and how well the immune system may fight it off. The tipping point at which cancer begins to overwhelm the immune system is not always known.

"There are lots of different reasons why that might happen," Dr. Lynch says. "Some of it has to do with the DNA of the tumor. Some of it has to do with the aggressiveness of the cancer."

Research has shown that cancer cells exert tremendous sway over some innate and adaptive immune cells and use them or recruit them to grow and travel to other parts of the body. Because cancer cells are the body’s own cells that have gone rogue, they have inside information on which signals to send to trick immune cells.

For instance, regulatory T-cells (T-regs) are like the immune system’s off switch. They’re designed to monitor an immune response and shut it down after the bad cells are vanquished.

But Japanese researchers have concluded that cancer cells can trick Tregs to shut down the immune response, allowing the cancer to proliferate.

Researchers also have found that cancer cells reach out to T-cells with long, hollow strands called nanotubes and extract matter from the immune cells’ mitochondria, literally sucking the life out of them.

For scientists, the challenge is to help strengthen immune cells against cancer without triggering an autoimmune disease or creating a “cytokine storm” that allows the immune system to start attacking healthy cells.

How may cancer immunotherapy help

You may help support your immune system by eating a healthy diet, getting plenty of restful sleep and exercising. But to help the body fight cancer, those steps and others may not be enough.

With some cancers, the immune system may need to be stimulated or amped up to better respond to cancer cells and recognize them as bad cells that need to be destroyed.

Enter immunotherapy.

Immunotherapy drugs are designed to help the immune system distinguish cancer cells from normal cells. Immunotherapy drugs cover a broad range of categories, including those listed below.

Checkpoint inhibitors: These drugs are designed to disrupt signals that cancer cells use to evade the immune system.

Cytokines: These natural proteins are synthesized and administered to help regulate and direct the immune system to attack cancer cells.

Vaccines: Unlike flu shots and other inoculates designed to prevent disease, cancer vaccines use drugs designed to reduce the risk of cancer by attacking viruses that cause cancer or stimulate the immune system in a specific part of the body.

CAR T-cells: Short for chimeric antigen receptor T-cells, CAR T-cells are immune cells that have been extracted from blood, re-engineered to attack cancer cells and then returned to the body.

Unlike chemotherapy and radiation therapy, which kill cancer cells directly, immunotherapy drugs don't attack cancer cells. Instead, they kick-start the body's powerful immune system.

"Immunotherapy is not going in there and killing the cancer cells,” Dr. Lynch says. “It's simply pulling the disguise off the cancer cell that's trying to hide and allowing the immune system to recognize it and do the job it’s designed to do.”

If you’ve been diagnosed cancer and are interested in a second opinion about your diagnosis and treatment plan, call us or chat online with a member of our team.