We use a core set of cookies to make our website work. We also use optional cookies to measure our site's performance, personalize content and provide social media features, including through our advertising and analytics partners. For the optional cookies, you can "Accept All" or "Reject All."

By using our site, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

Dr. Marlon Kleinman’s passion for art, science and religion run deep.

For Marlon Kleinman, MD, the roots of his love of art, science and religion, run deep. Watching his parents serve the community as a child, his extended family’s enduring love of music and several pivotal events in his life have shown just how his seemingly separate passions have interconnected to enrich both his life and his medical career serving patients.

“’I’m very intrigued by the connection between a person’s thoughts, emotions speech, and actions with their strength to fight illness. I love to apply the knowledge of medicine to the enhancement of people-to-people interaction.” Dr. Kleinman says, explaining how he eventually decided to become a hematologist/oncologist. “I couldn’t find that same juxtaposition in cardiology or gastroenterology.

“I observed my mentors spending a day reviewing bone marrow biopsies with hematopathology physicians engaging with heavy duty scientific discussion and data. And then on that same day they could have a family meeting and talk about 'end of life’ issues or meet with a metastatic cancer patient who’s very uneasy and just listen to them or work with them combatting anxiety.”

Reflecting on his two-plus decades of practice as one of the most prominent hematologists/oncologists in the Chicago area, Dr. Kleinman can see how the branches of his life intersect.

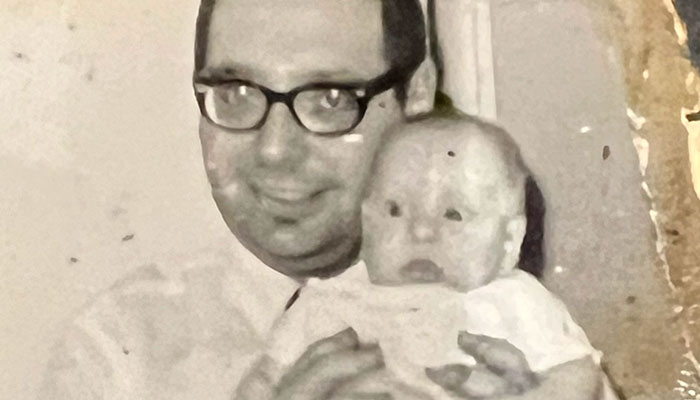

Dr. Kleinman’s father, Rabbi Norman Kleinman, was a key influence in his life. He clearly remembers his father’s bellowing voice—Rabbi Kleinman had dabbled in Shakespearean theater as a young man. His son recalls the power of his dad’s voice—even when he was speaking softly.

In performing his duties as a rabbi, Dr. Kleinman’s father modulated his voice and tone depending on the needs of the person he was addressing—something he thinks his father did subconsciously, knowing innately what the person he was counseling most needed from him in that moment.

“If someone were loud, anxious or angry, he would maintain respectful eye contact and speak softer. On the other hand, if they were withdrawn, he would increase his cadence and speak a little louder,” Dr. Kleinman remembers. Dr. Kleinman has long appreciated his father’s communication and counseling gifts but only recently began to emulate them, he admits. A much-beloved figure in his suburban Chicago community, his father died in 1999.

“The lessons I learned as a little kid watching my father interact with a wide spectrum of personalities continue to favorably influence my practice of medicine over the years,” Dr. Kleinman says.

This attention to voice extends throughout the family history. Dr. Kleinman’s great grandfather was a composer and cantor (a vocal performer of Jewish musical liturgy) in Jewish synagogues. A father to six children, his great-grandfather had hoped to pass his love of music onto his sons, but they were not interested. His daughters, however, gravitated to the music. Not to be silenced, they would sing his melodies often while sitting on the porch of their Borough Park, Brooklyn home.

“People would walk by and say, ‘Where’s that sound coming from?’” says Dr. Kleinman, relating the family lore. “In fact, one of my great aunts met her husband this way. That’s how my great-uncle became my great uncle.”

Dr. Kleinman inherited a good voice and a love of music, and, as a young boy he sang in a choir, and later played the trumpet. As an adult, he has fulfilled his great-grandfather’s dream and sings as a cantor in synagogue.

“My father encouraged me. Various teachers and directors encouraged me,” both in the theatrical arts and music. In our family, music was always a big experience.”

At the moment, Dr. Kleinman, his sister, Sara, who also sings, along with their cousins are working to record and preserve their great-grandfather’s musical compositions for the Passover Seder, which were the foundation of their holiday observations growing up.

When Dr. Kleinman arrived as a freshman at the University of Illinois, Champaign, in addition to biology, he studied music. However, he quickly found that the complexity of music theory classes pushed a much-loved art form into an academic chore.

“It was the first time I felt the dyssynergy between creativity and mathematics,” he recalls. “I very quickly changed my mind and diverted my path towards a career in medicine. I was into science. I wanted to deal with numbers, but I didn’t want that to interfere with the emotion of music—the pathos and the joy of music. So, I separated my passions.”

Perhaps surprisingly, his parents—especially his mom, who is in her 80s, is still a practicing therapist—urged him to reconsider his choice.

“They wanted me to consider less stressful paths,” Dr. Kleinman says. “My parents were very involved in my life and supportive of my choices and ultimately accepted that I ‘I’m doing this. I want to do medicine. I want to help people. I want to be a source of guidance and comfort.’ I wanted it to be on my terms. It was almost like a funny form of rebellion. The more I got involved in it, the more motivated and stimulated I became.”

In 1985, during his junior year as an undergraduate, Dr. Kleinman was involved in a high-speed motor vehicle accident that resulted in multiple bone fractures for which he required traction in the hospital for an extended period. This misfortune actually proved to be an unexpected convergence of the many branches of his life.

“It was around the time of the Jewish High Holy Days. I was supposed to sing in a synagogue that fall, but I ended up singing in the hospital,” thanks to the hospital staff organizing the services with some local rabbis, Dr. Kleinman says. He adds that physicians, nurses, support staff, “even people cleaning the rooms were part of this amazing experience and I was able to sing from my bed that Rosh Hashanah. That whole experience completely thrust me into medicine. It was an interaction between physicians and various staff and I was on the receiving end of all that. That was what really clinched the deal—this is really my life’s calling.”

While Dr. Kleinman says he strives to keep his religious and professional identities separate, he also knows that “there are some very basic life ideas, moral compass issues that play a role ubiquitously.”

He is a practicing orthodox Jew, wearing a kepah or head covering, and observing the Sabbath from Friday evening through Saturday, among other tenets of the faith, but his religious upbringing encompassed a wide diversity of viewpoints.

“My background is unique,” he says. “My father grew up in an orthodox Jewish home in Brooklyn, attending yeshiva (Jewish learning institution). In the 1960s and ran to the Catskills to explore the diversity of the community and perspectives around him. This is where he met my mother, a young liberal woman aspiring towards a career in social work. Consequently, the family emerging from their union has had exceptionally heterogeneous exposure to our community, ranging from the far-right wing, orthodox Judaism to very far left and assimilated sector plus everything in between.”

Dr. Kleinman attended public school, not Jewish day schools, and while his parents encouraged exploration of the full spectrum of Jewish religious observance and culture, they also imbued Dr. Kleinman, his sister and brother with a proud sense of their history

“Most of us in the end discovered our own sense of appreciation for our tradition,” Dr. Kleinman says, adding that the openness with which he was raised allows him to appreciate diversity. “I live an orthodox life now, but I find that because my siblings and I had such a broad-based influences, we can deal with all sorts of people. We’re comfortable in so many circumstances, whether it’s religious circumstances or just life circumstances, dealing with all sorts of people that maybe completely different than we are.”

The obligation to “judge others favorably” is a Jewish principle discussed by rabbinic scholars in the Talmud, Dr. Kleinman says, one that he tries to extend it to all facets of his life, including in caring for patients with cancer. Many times, in dealing with the physical and psychological impacts of the disease, patients may be irritable or short-tempered or appear to have given up on taking care of their appearance.

“You have to take a step back and say to yourself, ‘what are they going through?’ Pretend for a moment that their behavior is a fever. If the guy had a fever, you wouldn’t judge him,” he says. “What’s really fascinating is, if you approach a patient like that, it’s incredible watching the change in their behavior as part of the “healing progress”.

Dr. Kleinman’s sensitivity and positive outlook on life extends to his patients at City of Hope® Cancer Center North Shore in other ways as well, showing just how he can meld the rigors of science with the human dimension of being an oncologist.

Thanks to immunotherapy and targeted therapy, many malignant conditions can be treated with positive outcomes, allowing cancer patients to live longer than they might have in years past. This is great news, but Dr. Kleinman appreciates the emotional aspects of how this sometimes plays out with his patients.

“They’re struggling with the concept that they have the … cancer still because it’s true. It’s not cured. So, then they become victimized by the presence of the disease, even though the disease is stable and not progressing,” he says. Patients struggle with their imperfections and consequently their perceived limitations.

“I sit with those people and try to motivate them by asking questions like, for example, ‘what would you do if you didn’t have lung cancer?’ It’s incredible to hear the responses of what they would do. So, I prescribe—precisely to ‘do those things. I want you to act as if you don’t have it.’ This is a very important way for providers to better understand how cancer destroys …where patients are so glued to the stigma of their disease that they can’t let go, struggling to fully embrace the joy in life.”