We are living in an incredible age of cancer care. Advanced genomic testing gives doctors a deep dive inside cancer cells and the gene mutations or biological features that may be driving a tumor’s growth. Targeted therapy drugs have been developed to attack those mutations and are designed to spare healthy cells. Immunotherapy drugs, designed to strip away cancer cells’ ability to hide from the immune system, are standard-of-care treatment for many difficult cancers, including lung cancer and melanoma.

But, despite these incredible advancements, one of the most hard-to-treat cancers continues to vex doctors and researchers: pancreatic cancer.

“It’s a very difficult cancer,” says Maurie Markman, MD, President of Medicine & Science, City of Hope® Cancer Centers Atlanta, Chicago and Phoenix. “The location of the pancreas, including being surrounded by a number of vital structures, makes pancreatic cancer difficult to both diagnose and treat surgically. Plus, pancreas cancers are, for a variety of reasons, quite resistant to most available systemic anti-cancer agents.”

Pancreatic cancer cells are particularly evasive and resilient for a number of reasons, including:

- Pancreatic cancer is often asymptomatic in early stages and almost half of all cases are diagnosed in stage 4.

- Most pancreatic cancers are driven by cell mutations in the KRAS gene, for which no current treatments are available.

- Pancreatic tumors entangle themselves into surrounding blood vessels and tissue, making surgical removal difficult.

- The tumors often cocoon themselves in fibrous tissue that is difficult for chemotherapy drugs to penetrate.

- The pancreatic tumor microenvironment is believed to suppress immune cells, making immunotherapy treatments often ineffective.

In this article, we’ll explore these five main reasons pancreatic cancer is so difficult to treat. We’ll also detail some promising new treatments and the reasons why pancreatic cancer survival rates are improving.

If you or a loved one has been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and you’re interested in a second opinion on your diagnosis and treatment plan, call us or chat online with a member of our team.

Why is pancreatic cancer so hard to treat?

Pancreatic cancer is the 10th most common cancer in the United States, with more than 64,000 cases expected to be diagnosed this year, according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Several NCI statistics illustrate the challenges of this disease:

The average age of a patient diagnosed with pancreatic cancer is 70; the average age of a patient who dies from the disease is 72.

The five-year survival rate of a person diagnosed with metastatic pancreatic cancer is just 3.2 percent.

Pancreatic cancer accounts for 3.3 percent of all new cancer diagnoses, but 8.3 percent of all cancer deaths, third only behind lung and colorectal cancers.

The rates of new cases and deaths from cancer of the pancreas have remained virtually flat for more than 30 years. The death rate is 11 per 100,000 people; the rate of new cases is 12 per 100,000.

The lack of movement frustrates researchers, doctors and patients alike. Experts and health care professionals know many of the reasons why pancreatic cancer is difficult to treat, but they have not yet found breakthroughs to attack them.

Late pancreatic cancer diagnosis

Pancreatic cancer is detected in stage 4 of the disease—an advanced form of the cancer—more than half the time. Often, by the time it is diagnosed, the cancer has already spread to the liver or other parts of the body, making it more difficult to treat effectively.

“Even in patients who have been diagnosed with early-stage pancreatic cancer, it tends to be notoriously challenging,” says Daniel Bruetman, MD, Medical Oncologist at City of Hope in Downtown Chicago.

The five-year survival rate for patients with localized pancreatic cancer is 44 percent, according to the NCI, far lower than rates for other common cancers, including breast (99 percent), prostate (100 percent), colorectal (91 percent) and lung (63 percent).

Warning signs of pancreatic cancer may include:

- Dark urine

- Weight loss

- Digestive issues

- Nausea

Other symptoms include:

- Abdominal or back pain

- Extreme fatigue

- Swelling and bloating

- Jaundice

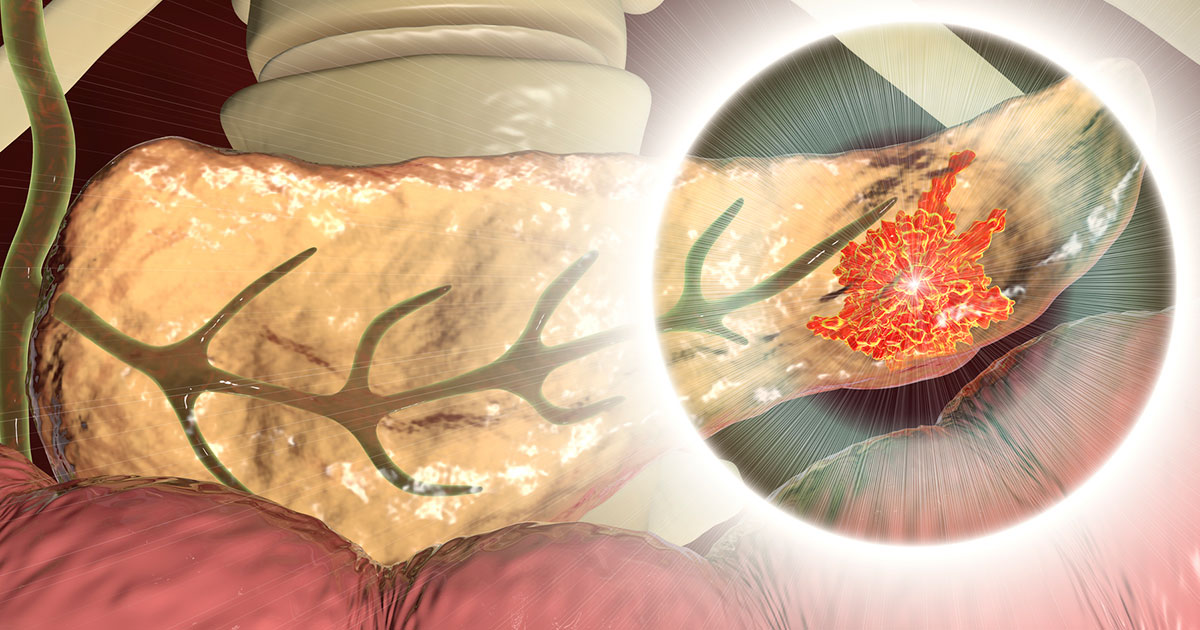

Pancreatic tumors are often inoperable

Pancreatic tumors are particularly invasive in the abdomen and often cannot be completely removed during surgery. In some cases, they become so entangled in blood vessels that feed other vital organs that surgery is no longer a viable option.

One surgical treatment is called the Whipple procedure, in which surgeons remove the pancreas, or part of the organ, and rebuild the digestive system. This is a complex, multi-stage surgery in which the gallbladder, bile duct, associated lymph nodes and part of the stomach are also removed. Patients may need to take insulin and digestive enzymes after Whipple surgery, since the body no longer produces these substances on its own.

“It's a pretty drastic surgery, but nowadays it's changed tremendously,” Dr. Bruetman says. “We used to refer to it as a high-risk, high-mortality surgery. But in patients who are relatively healthy, they can do very well with it.”

Still, the five-year survival rate for patients who have received the Whipple procedure is about 25 percent.

Tumors form a shield of armor

Pancreatic cancer cells create a cocoon of collagen fibers around the tumor that shield it from the body’s immune system and some treatments. These fibers, which are like scar tissue, form when cancer cells produce enzymes that damage healthy tissue, leading to the formation of collagen that eventually envelopes the tumor. This process is called desmoplastic reaction, or desmoplasia, and is a feature of several cancers. Meanwhile, the immune system or chemotherapy doesn’t make it through the barrier because it’s too hard to penetrate.

Cancers often have biomarkers with no targeted therapies

In cancer, biomarkers are genetic features or mutations in cells that may drive a tumor’s growth. The identification of some biomarkers has led to the discovery of targeted therapy and immunotherapy drugs designed to attack tumor cells via those biomarkers. Pancreatic tumors often are driven by mutations in the KRAS and TP53 genes, two of the most common markers found in tumors. Last year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first targeted therapy for locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancers that contain the KRAS mutation with a G12C variant. This drug has not been approved for pancreatic cancer.

Immunotherapy not usually an option

While some tumors contain dormant immune cells called lymphocytes that may be awakened by immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors, pancreatic cancer cells are low in immunogenicity and are less likely to generate an immune response.

However, immunotherapy may be a treatment option for pancreatic cancers when a tumor has multiple genetic or genomic abnormalities, several of which may be driving the cancer’s growth (known as a high tumor mutational burden).

Pancreatic cancer advancements

As persistent as pancreatic cancer cells are to resisting treatment, so are doctors and researchers in searching for new diagnostic tests and treatments. And their persistence may be paying off. The overall five-year survival rate for patients with pancreatic cancer has nearly doubled from 7 percent to 13 percent over the past decade.

“Novel approaches for both early diagnosis and treatment continue to be aggressively pursued,” Dr. Markman says. “I suspect that one or more of these strategies will soon begin to substantially change suspected outcomes for patients diagnosed with this cancer.”

Among the new developments in the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer are those listed below.

Exosomes: These tiniest of vesicles are like carrier pigeons delivering messages from one cell to another. These messages often include instructions that give cells new duties to perform. In cancers, researchers have found evidence that tumors use exosomes to turn healthy cells into cancer cells, suppress the immune system and help cancers grow and resist treatment. Researchers know exosomes play a role in pancreatic cancer and are studying how they may be used to help diagnose and treat pancreatic tumors.

Vaccines: Researchers around the world are exploring pancreatic cancer vaccines designed to jump-start an immune response in pancreatic tumors. These vaccines—some of which are RNA-based—could be used in addition to surgery to help prevent or delay a recurrence of the disease. In one case, researchers found “patients with vaccine-expanded T-cells had a longer median recurrence-free survival compared with patients without vaccine-expanded T-cells.”

Liquid biopsies: A team of researchers, including those from City of Hope and its affiliate Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen), have made strides in studying a simple blood test that may help to detect pancreatic cancer early. The test is designed to detect small amounts of RNA genetic material from pancreatic cancer cells that circulates in the bloodstream.

Early results “highlight the urgent, unmet clinical need to identify and develop diagnostic methods that could precisely detect pancreatic cancer at its earliest stages, when the disease is still confined to the pancreas and surgical resection is still an option,” says Ajay Goel, Ph.D., Professor and Chair, Department of Molecular Diagnostics and Experimental Therapeutics at City of Hope and the study’s senior author.

If you or a loved one has been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and you’re interested in a second opinion on your diagnosis and treatment plan, call us or chat online with a member of our team.