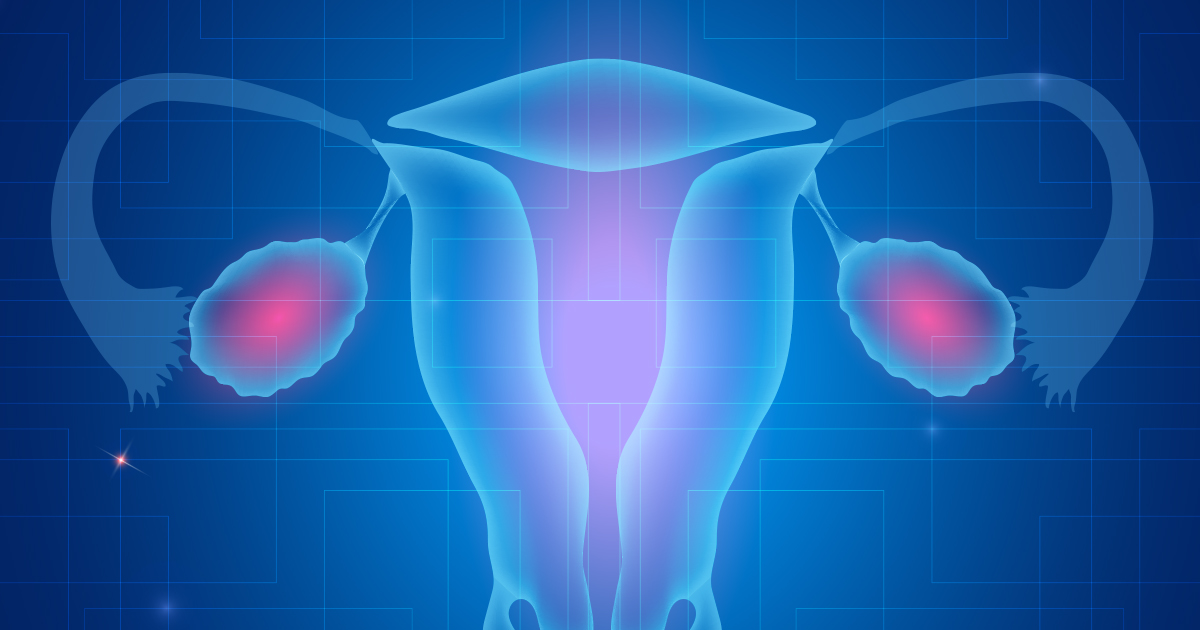

A recent ovarian cancer study corroborates what gynecologic oncologists have suspected for at least a decade: The most common type of ovarian cancer likely begins in the fallopian tubes. The findings corroborate the long-held suspicion that abnormal changes in fallopian tube tissue may be precursors to the most common type of ovarian cancer, high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas (HGSOC), which accounts for about 75 percent of all ovarian cancers.

In an analysis of multiple tumor samples from nine women with HGSOC, researchers at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center found that the majority of gene mutations in the tumors actually developed years before, as abnormal changes in the fallopian tissue, called fallopian tube lesions. Experts hope the findings help advance developments in early detection, treatment and even prevention.

“Cells that line the fallopian tube are called serous cells, and they produce watery, serous fluid. Serous ovarian carcinoma is the most common type of ovarian cancer. It turns out that most serous ovarian carcinomas probably actually start in the serous cells that line the fallopian tube. All of a sudden, the way ovarian cancer behaves starts to make a lot more sense. The cells in the fallopian tube can float out and implant anywhere in the abdominal cavity.” - Julian Schink, MD, Chief of Gynecologic Oncology at Cancer Treatment Centers of America® (CTCA)

What do the fallopian tubes do?

The fallopian tubes connect the ovaries to the uterus, and because the organs are so intertwined, the disease is usually diagnosed as ovarian cancer. “This is because the organs live side by side, and once the fallopian tube is involved, cancer spreads quickly to the ovary, and then it’s impossible to tell where it started,” Dr. Schink says.

Ovarian cancer causes more deaths than any other gynecologic cancer, so understanding how it evolves may be game-changing, particularly since about 70 percent of ovarian cancer patients are not diagnosed until the disease has already progressed to an advanced stage. “For so long, people have been frustrated that ovarian cancer spreads so early, but of course it does, because it’s a free-floating cell in the fallopian tube,” Dr. Schink says. “These studies continue to give us new strategies for early detection, which hopefully leads to better treatments.”

It makes sense, he says, that fallopian tube lesions may be a harbinger for ovarian cancer, considering that ovarian cancer incidence rates are far lower in women who have had their tubes removed, or who have undergone a hysterectomy or a tubal ligation, a surgical procedure that cuts or ties the fallopian tubes together to permanently prevent pregnancy.

When to talk to your doctor

Dr. Schink recommends that women who carry an inherited BRCA mutation, or who have a family history of ovarian cancer, talk with their doctor about options to reduce their ovarian cancer risk. “Be aware that removing the fallopian tubes at a younger age significantly reduces the risk of cancer,” Dr. Schink says. “The data says there’s at least a 50 percent reduction. Anyone considering surgical tubal ligation should consider having their entire fallopian tubes removed to further lower their risk.” The fallopian tubes act as a conduit between the ovaries and the uterus, which is important to women who want to conceive. But, thanks to advances in reproductive medicine, in vitro fertilization allows some women of child-bearing age to become pregnant even after having their tubes removed.

Since ovarian cancer is rarely detected during a Pap smear, and no other screening tools have been developed for the disease, Dr. Schink recommends women pay close attention to their bodies for possible symptoms. “About 95 percent of women with ovarian cancer report symptoms,” including bloating, a distended abdomen, abdominal pain, changes in bowel movements and more frequent urination, says Dr. Schink. By the time these signs develop, the disease has often advanced beyond the early stages, so women should talk to their doctor as soon as they notice the changes.

Researchers in the Johns Hopkins and Dana-Farber study found that a fallopian tube lesion took an average of six-and-a-half years to develop into ovarian cancer, but it took just two years for the cancer to metastasize or spread to another part of the body. The study’s lead author, Victor Velculescu, MD, PhD, co-director of Cancer Biology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, noted that with nine patients, the sample size was small, but added that "if studies in larger groups of women confirm our finding that the fallopian tubes are the site of origin of most ovarian cancer, then this could result in a major change in the way we manage this disease for patients at risk.”