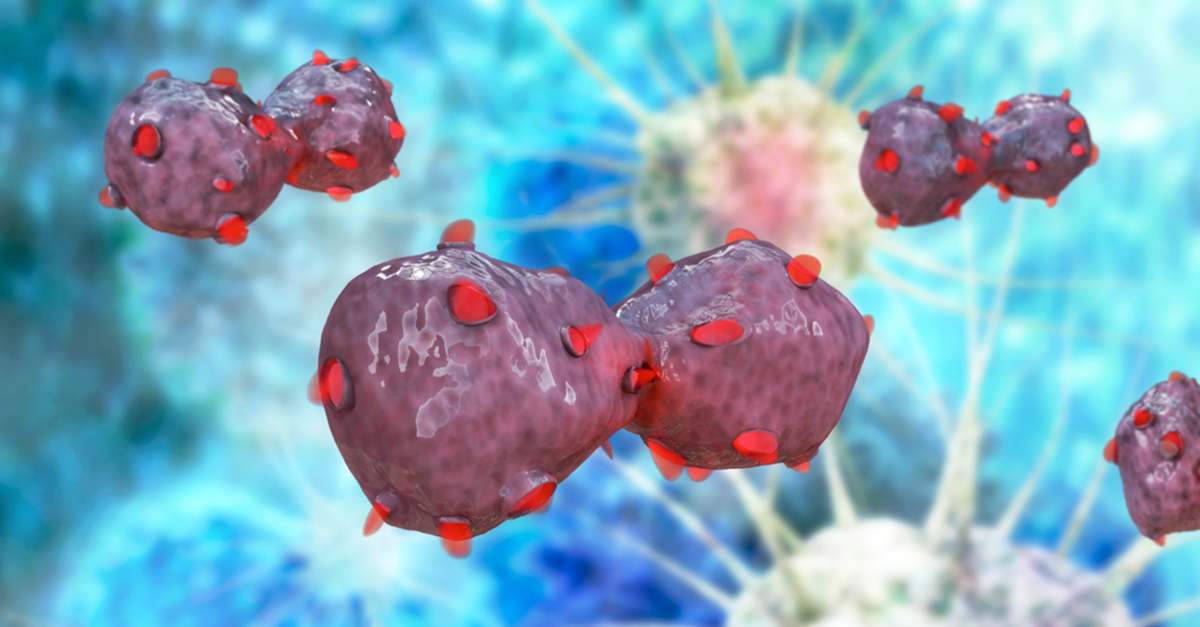

If you’ve ever relied on a copy machine, you know what happens when it goes on the fritz. Whether it's low on toner, has a paper jam or turns your original into something resembling an accordion, the results can ruin your work product. On a much more consequential scale, similar breakdowns occur in the human body, which is responsible for churning out billions of replicas of new cells every day. With so many reproductions being made at once, something's bound to go wrong. When it does, cancer may form. In fact, according to a new study, it often does.

"We're not perfect," says Dr. David Boyd, Intake Physician at our hospital near Phoenix. "We're living organisms, and things don't always go to plan. We know how our molecules are supposed to be, but they don’t always go that way." As part of mitosis, a life-sustaining process that replenishes the cells of the skin, tissue, organs and other matter, all the cells of the body make two copies of themselves. A new study by researchers at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine concludes that replication errors in that process may be responsible for more than 60 percent of all cancers. "Each time a normal cell divides and copies its DNA to produce two new cells, it makes multiple mistakes," study co-author Cristian Tomasetti, of Johns Hopkins, told The Hub, a Johns Hopkins University blog. "These copying mistakes are a potent source of cancer mutations that historically have been scientifically undervalued."

Random errors, lifestyle and genetics

The study, which examined 32 cancer types, also concluded that:

- Most cases of pancreatic cancer—77 percent—are caused by random cell replication errors. The rest may be traced to environmental factors or genetics.

- Nearly all cases—95 percent— of prostate, brain or bone cancers are linked to errors in cell copies.

- Most lung cancer cases are caused by tobacco smoking. Only about 35 percent of lung cancers are attributed to cell replication errors.

- Sixty-six percent of all cancer-related mutations are linked to copying errors; 29 percent are traced to lifestyle or environmental factors; 5 percent are caused by genetics.

"This falls into the category of life where things just happen and you don't have an explanation for it," Dr. Boyd says. "Certainly, we have patients who do all the right things. They eat right. They exercise. They ate organic before organic became common parlance, and they still ended up with cancer. It's common for people, when they get diagnosed, to want to find out what they did wrong. But sometimes, you look for a reason and it's just not there."

Fixing bad copies

Just because a cell spits out a bad copy doesn't mean it will cause cancer. Most irreparably bad cells kill themselves. But first, the body works to fix them. One way cells monitor damage is with a protein called poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP). This enzyme acts as a cellular construction foreman and directs genetic repair crews to fix damaged DNA. "We are amazing organisms," Dr. Boyd says, "and we have a proofreading system that checks for these problems. And it fixes about 99 percent of those. And that's usually good enough for normal cell function."

Random mutations, genetics and cell replication errors aside, there are a number of measures people can take that may help prevent cancer, Dr. Boyd says. "You don't want to up the ante," he says. "You don't want to have extraneous factors that can still increase your chances. It's all the more reason to do all the right things: eat well, exercise, reduce stress, see your doctor on a regular basis, use sun screen and practice safe sex." Dr. Bert Vogelstein, co-author of the Johns Hopkins study and co-director of the Ludwig Center at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, says cancer prevention should remain a focus, but added that his research underscores the need for better early detection. "We need to continue to encourage people to avoid environmental agents and lifestyles that increase their risk of developing cancer mutations," he told The Hub. "However, many people will still develop cancers due to these random DNA copying errors, and better methods to detect all cancers earlier, while they are still curable, are urgently needed."