This page was reviewed under our medical and editorial policy by

Maurie Markman, MD, President, Medicine & Science

This page was updated on September 12, 2022.

When a patient is diagnosed with leukemia, the care team will identify the specific type of leukemia to help guide treatment decisions.

Leukemia is classified by the type of white blood cells affected and by how quickly the disease progresses:

In terms of how quickly it develops or gets worse, leukemia is classified as either acute (fast-growing) or chronic (slow-growing):

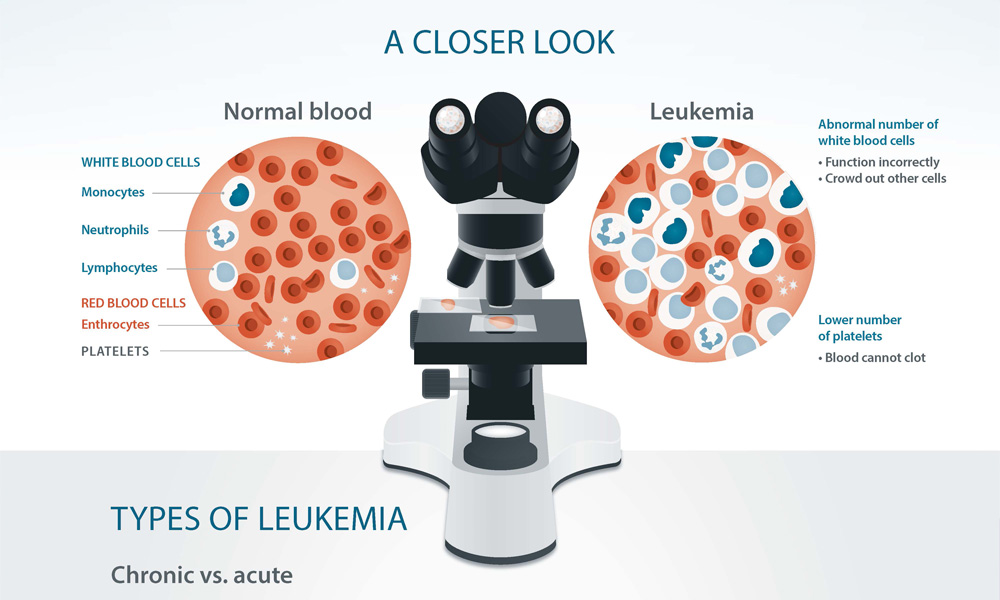

During the leukemia diagnosis process, the care team may analyze a sample of the patient's blood to evaluate whether they can detect any abnormal cells.

Download leukemia infographic »

According to data from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, the most common types of leukemia in the United States are, in this order:

ALL develops when changes in DNA (mutations) cause the bone marrow to produce too many abnormal lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell). Lymphocytes are supposed to help fight infections, but the ones produced in people with ALL are unable to do so properly. The proliferation of these abnormal cells also crowds out other types of healthy blood cells.

It’s unknown what exactly causes the mutations that lead to ALL, but certain factors may increase one’s risk. Risk factors for ALL include:

Acute lymphocytic leukemia may be diagnosed with blood tests and a bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, which involve extracting a sample of bone marrow and a tiny piece of bone, then studying the cells under a microscope.

Some of the common treatment options for ALL include:

Acute myeloid leukemia, also known as acute myelogenous leukemia, acute myeloblastic leukemia, acute granulocytic leukemia or acute nonlymphocytic leukemia, is a fast-growing form of cancer of the blood and bone marrow.

Like ALL, AML causes the bone marrow to overproduce abnormal white blood cells, crowding healthy blood cells and affecting the body’s ability to fight infections.

Risk factors for AML include:

Some symptoms of AML may resemble the flu—such as fever, fatigue and night sweats. Others include easy bruising or bleeding and weight loss. Blood tests and bone marrow aspiration and biopsy are among the tests that may be done to diagnose this cancer.

Treatment may include:

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is a typically slow-growing cancer that begins in lymphocytes in the bone marrow and extends into the blood. It may also spread to lymph nodes and organs such as the liver and spleen. CLL develops when too many abnormal lymphocytes grow, crowding out normal blood cells and making it difficult for the body to fight infection.

About 25 percent of all cases of leukemia are CLL, and approximately one in every 175 people may develop CLL in their lifetime, according to the American Cancer Society (ACS). CLL is like ALL, but it’s chronic instead of acute, meaning that it’s more slow-growing and takes longer to start causing symptoms.

When CLL does cause symptoms, these may include swelling in the lymph nodes (neck, underarm, stomach or groin), fatigue, fever, infection, weight loss and more. Various blood tests may be used to help diagnose CLL.

CLL may not need to be treated immediately, but rather monitored for any problems and changes, at which point the need for treatment may be reassessed. Common treatment options include:

Chronic myeloid leukemia, also known as chronic myelogenous leukemia, begins in the blood-forming cells of the bone marrow and then, over time, spreads to the blood. Eventually, the disease spreads to other areas of the body.

CML is slow-growing, but once it starts causing symptoms, these may include fatigue, fever, weight loss and an enlarged spleen. Around half of CML cases are diagnosed by a blood test before symptoms have begun. About 15 percent of leukemias are CML, according to the ACS.

Treatment options include:

Among the many different types of leukemia, some are less common than others. Three rarer leukemia types—prolymphocytic leukemia (PLL), large granular lymphocyte leukemia (LGL) and hairy cell leukemia (HCL)—share some of the same characteristics as lymphocytic leukemias and are sometimes considered subtypes of chronic or acute lymphocytic leukemia (CLL and ALL). Myelodysplastic syndromes are conditions related to leukemia that are also rare.

Prolymphocytic leukemia (PLL) may develop along with CLL or on its own, but it usually progresses faster than typical CLL. It’s marked by a proliferation of immature lymphocytes. If PLL causes symptoms, they may be similar to other types of leukemia (flu-like symptoms, easy bruising, unexplained weight loss). A PLL diagnosis may include blood tests as well as bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. PLL tends to respond well to treatment, and options may resemble those used to treat CLL. However, relapse is common.

Large granular lymphocytic (LGL) leukemia is a chronic type of leukemia that causes the body to produce abnormally large lymphocytes. By the time patients are diagnosed with this condition, symptoms tend to be present and include flu-like symptoms, frequent infections and unexplained weight loss. People with autoimmune diseases tend to be more at risk for developing LGL. A diagnosis of LGL leukemia may include blood tests and bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. Most patients require treatment shortly after diagnosis, which may include drugs that suppress the immune system. Others may be able to hold off on treatment to see whether problems arise. Treatment for LGL isn’t standardized, and patients may require different options, depending on their condition.

Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) is a rare subtype of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) that progresses slowly. About 700 people are estimated to be diagnosed with HCL every year, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology. HCL is caused when bone marrow makes too many B cells (lymphocytes), a type of white blood cell that fights infection. As the number of leukemia cells increases, fewer healthy white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets are produced. The word “hairy” comes from the look of the cells produced. Under a microscope, HCL cells appear to have thin, hair-like outgrowths.

Hairy cell leukemia symptoms may be similar to other types of leukemia and resemble the flu. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy and blood tests are the primary diagnostic tools.

HCL often doesn’t need to be treated immediately, and patients are monitored for problematic changes that require treatment. When complications related to HCL do occur—such as low blood cell counts, frequent infections or lymph node swelling—chemotherapy is typically used.

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a group of closely related diseases in which the bone marrow produces too few functioning red blood cells (which carry oxygen), white blood cells (which fight infection), or platelets (which prevent or stop bleeding), or any combination of the three. The different types of myelodysplastic syndromes are diagnosed based on certain changes in the blood cells and bone marrow. The cells in the blood and bone marrow (also called myelo) usually look abnormal (or dysplastic), hence the name myelodysplastic syndromes.

Approximately 10,000 people a year are diagnosed with MDS, according to the ACS. In the past, MDS was commonly referred to as a preleukemic condition (and it is still sometimes called preleukemia) because some people with MDS develop acute leukemia as a complication of the disease. However, most patients with MDS never develop acute leukemia.

By convention, MDS are reclassified as acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with myelodysplastic features when blood or bone marrow blasts reach or exceed 20 percent.