This page was reviewed under our medical and editorial policy by

Daniel Liu, MD, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeon

This page was reviewed on February 18, 2022.

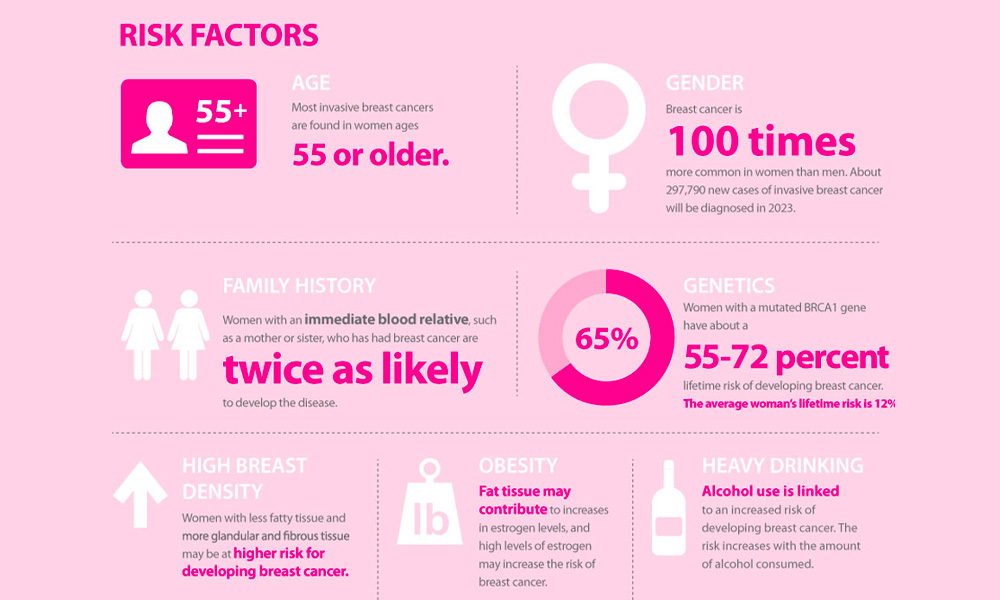

When it comes to breast cancer risk, there are factors you can’t change, like your age, race and genes. But there are others you do have control over, such as your exercise level, alcohol consumption and other lifestyle habits.

Breast cancer is caused when the DNA in breast cells mutate or change, disabling specific functions that control cell growth and division. In many cases, these mutated cells die or are attacked by the immune system. But some cells escape the immune system and grow unchecked, forming a tumor in the breast.

The key to lowering your risk for breast cancer is to focus most of your prevention efforts on those modifiable risk factors, and to be proactive in various ways to monitor the ones you can’t change.

The American Cancer Society (ACS) estimates that a woman’s chance of developing breast cancer during her lifetime is about 13 percent. That translates to a 1 in 8 chance of developing breast cancer. At the same time, it means there is a 7 in 8 chance that you won’t develop breast cancer.

In terms of cancers that affect women, 1 in 3 are breast cancer. The ACS reports that the incidence of a woman developing breast cancer has risen by 0.5 percent per year in recent years.

Risk factors are characteristics and conditions that increase your risk for a disease. Breast cancer risk factors include some you cannot change, such as having a family history of breast cancer, being a woman and getting older. But there are other risk factors that you can change to help lower your likelihood of developing breast cancer. Doctors don’t know why some women with risk factors don’t get breast cancer and why others with no risk factors, other than being female, do get breast cancer. Still, you can make certain lifestyle choices to try to lower your risk.

Download breast cancer infographic »

Your risk for breast cancer may rise with every drink. Research suggests that women who drink one alcoholic beverage a day have a 7 to 10 percent increased risk for breast cancer compared with non-drinkers, and this number jumps to 20 percent for those who have two to three alcoholic drinks per day, according to the American Cancer Society.

Reduce your risk: For women, moderate drinking means no more than one drink per day. If you’re a daily drinker, start by cutting back to just a few times a week. Also, become aware of how much you’re drinking: A standard drink is about 14 grams of alcohol—that’s 12 ounces of regular beer, 5 ounces of wine or 1.5 ounces of distilled spirits. If you’re filling an oversized glass, that one drink could really count as two.

Breast cancer is on the list of diseases and conditions caused or worsened by being overweight or obese after menopause. Your ovaries stop making the female sex hormone estrogen after menopause, so most estrogen comes from fat tissue. The more fat you have, the more estrogen you make, and estrogen feeds some breast cancers, causing them to grow. Women who are overweight also may have higher blood insulin levels, which have been linked to breast cancer and diabetes.

Reduce your risk: Consider working with a dietitian to find a weight loss plan, one with lots of fruits and vegetables, that works for your lifestyle, making it more likely that you’ll stick with it. Being at a healthy weight really helps. Women who lose weight after age 50 and keep it off have a lower risk of breast cancer than women whose weight stays the same. And the more weight you lose, the lower your risk. Women who lost about 4.4 to 10 pounds had a 13 percent lower risk than women who didn’t lose weight, while those who lost 10 to 20 pounds had a 16 percent lower risk, and those who dropped more than 20 pounds had a 26 percent reduced risk of breast cancer, according to a large study in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The less you move, the higher your risk for breast cancer.

Reduce the risk: Staying physically active may help decrease your chances of developing breast cancer and other diseases—and aid in weight-loss efforts. The American Cancer Society recommends that you aim for 150 to 300 minutes of moderate intensity exercise, such as brisk walking, or 75 to 150 minutes of more intense activity, like running, each week. The more physical activity you do, the greater the benefits. Get the all-clear from your doctor before making major changes to your exercise regimen.

Women who haven’t had children, or who had their first child after age 30, may have a slightly higher chance of developing breast cancer. That’s because breast tissue is exposed to more estrogen for longer periods of time. The risk of breast cancer declines for women who become pregnant at a younger age and those with a higher number of births.

What to do: Discuss your reproductive history with your doctor when considering your breast cancer screening and prevention plan.

If you started menstruating before you turned 12, you are at higher risk for breast cancer because of the increased number of years that your breast tissue has been exposed to estrogen. Entering menopause late (after age 55) also ups the risk, for similar reasons.

What to do: Discuss your menstrual history with your doctor when reviewing your breast cancer screening options.

If you breastfed, your risk of developing breast cancer may be reduced, especially if you did it for a year or longer. Breast cancer reduction is just one of many benefits associated with breastfeeding. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends breastfeeding for about the first six months of life, then continuing to breastfeed, supplementing with appropriate foods, for one year or longer.

What to do: Consider breastfeeding, if possible, as it also protects your baby from many diseases.

Some birth control methods use hormones, which can up breast cancer risk. These may include:

Using combined hormone therapy after menopause increases the risk of developing breast cancer. Combined HT also increases the likelihood that the cancer may be found at a more advanced stage.

What to do: Discuss concerns with your doctor and weigh all the risks and benefits to make the right decision about birth control or hormone replacement therapy.

Be aware of potential breast cancer risks that are not yet proven, such as high-fat diets, certain pesticides, and chemicals found in personal-care products. There’s also some evidence to suggest that working the night shift increases breast cancer risk. Researchers are actively studying these potential risk factors.

Science has largely debunked other factors, including using antiperspirants, wearing underwire bras and having had an abortion. Many women also worry about hair dye and breast cancer risk. However, according to the National Cancer Institute, a review of data from 14 studies found no conclusive evidence that women who use hair dye face increased risk of breast cancer compared with women who don’t dye their hair.

During your next doctor’s visit, discuss your risk factors to make sure you’re doing all you can to prevent breast cancer. Your visit could include reviewing one of the assessment tools available to estimate your risk of getting breast cancer in the next five years and over your lifetime.

If you’re at increased risk, your doctor may suggest earlier screening, more regular or intensive screening, and possibly medications.

While men may develop breast cancer, it’s rare. Women are at much higher risk.

What to do: Focus on the risk factors that you can change, such as maintaining a healthy body weight and getting regular physical activity.

Breast cancer risk rises with advancing age. Most breast cancers are found in women age 55 and older.

What to do: Regular breast cancer screening exams with mammography won’t prevent breast cancer, but they may find it earlier, when it’s more treatable. Discuss the best schedule for your breast cancer screening with your doctor.

You don’t need a family history to develop breast cancer. In fact, just 15 percent of patients have had a family member with this disease. That said, if you have first-degree relatives (parent, siblings or children) with a history of cancer, you are considered at higher risk.

What to do: If your mother, sister or daughter has had breast cancer, your risk is almost doubled. With two first-degree relatives with breast cancer, your risk increases about threefold. Having a father or brother with breast cancer also increases your risk. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), you’re also at somewhat higher risk if you have a first- or second-degree relative with high-grade prostate cancer.

Make sure your family history is a factor in your breast cancer screening decisions. It may make sense for you to see a genetic counselor and get tested for known breast cancer genes.

Up to 10 percent of breast cancers may be inherited via gene changes or mutations passed on from your parents, such as the BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Researchers are trying to uncover additional genes that may be involved in breast cancer risk.

What to do: Speak with a genetic counselor about whether to get tested for the known breast cancer genes. Genetic counseling and/or testing for BRCA gene mutations is suggested for people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. If you have these mutations, discuss medication or surgical options to reduce that risk. For example, a preventive bilateral mastectomy may reduce your chances of developing breast cancer by 90 percent or more, according to the American Cancer Society.

If you’ve been diagnosed with breast cancer in the past, you are more likely to develop a new cancer in the other breast or in another part of the same breast. This is not considered a recurrence but a new breast cancer.

What to do: Follow your cancer team’s instructions on monitoring to stay on top of this risk. Ask your doctor whether you should see a genetic counselor.

White and Black women have the highest risk of developing breast cancer in their lifetime. Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic/Latina women’s breast cancer rates fall in between two major groupings while American Indian and Alaska Native women are on the lowest end of risk.

While white women are more likely to develop breast cancer than Black women overall, they tend to be diagnosed at an older age (between 60 and 84). Black women have the highest breast cancer rates among women under age 40. Black women make up a higher percentage of triple-negative breast cancer cases.

What to do: If your race or ethnicity places you at higher risk, make sure you follow all screening recommendations to improve your chances of catching cancer early.

Taller women are more likely to develop breast cancer than their shorter counterparts. Researchers aren’t sure why this is the case.

Dense breasts have more glandular and fibrous tissue and less fatty tissue, and this is known to increase your chances of developing breast cancer. Dense breast tissue also may make it harder to visualize breast cancers on mammograms.

What to do: If you have dense breasts, which must be noted in your medical records, ask your doctor which screening options are most suited for you. This may include other imaging techniques along with mammograms.

Certain noncancerous breast conditions may confer a higher risk of developing breast cancer. The list includes proliferative lesions without cell abnormalities such as usual ductal hyperplasia, fibroadenomas, sclerosing adenosis, several papillomas and radial scars. Proliferative lesions with cell abnormalities, including atypical ductal hyperplasia and atypical lobular hyperplasia, also increase risk.

What to do: Knowledge is power. If you have a history of any of these benign breast conditions, make sure your doctor is aware and that this information is considered when making decisions about how and when you should screen for breast cancer.

If you had another type of cancer and received radiation therapy to your chest as part of your treatment plan, you may be at higher risk for breast cancer.

What to do: Any history of radiation to your chest should be considered when devising a breast cancer screening plan.

From the 1940s through the early 1970s, some pregnant women were given an estrogen-like drug called DES to lower their chances of having a miscarriage. This may increase chances of breast cancer for moms who took it, and possibly for their kids, too.

What to do: If you or your mom took DES to stave off miscarriage, inform your doctor and discuss how it factors into your screening plan.

According to the CDC, you are considered high risk for breast cancer if you have:

These two risk factors also put you at a high risk for ovarian cancer. Speak with your doctor about what you can do to reduce your risks. Options include drugs that block or decrease estrogen in your body and preventive surgery.